By Matthew Rae, Gary Claxton, Krutika Amin, Emma Wager, Jared Ortaliza, and Cynthia Cox

March 10, 2022 - Peterson-KFF Health System Tracker

Despite over 90% of the United States population having some form of health insurance, medical debt remains a persistent problem. For people and families with limited assets, even a relatively small unexpected medical expense can be unaffordable. For people with significant medical needs, medical debt may build up over time. People living with cancer, for example, have higher levels of debt than individuals who have never had cancer.

High deductibles and other forms of cost sharing can contribute to individuals receiving medical bills that they are unable to pay, despite being insured. People with medical debt report cutting spending on food, clothing, and other household items, spending down their savings to pay for medical bills, borrowing money from friends or family members, or taking on additional debts.

In this brief, we analyze data from the Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) to understand how many people have medical debt and how much they owe. A recent Census Bureau analysis on medical debt at the household level found 17% of households owed medical debt in 2019. Here, we analyze medical debt at the individual level for adults who reported owing over $250 in unpaid medical bills as of December 2019. We focus on people with over $250 in medical debt, a threshold we define as “significant” medical debt to distinguish from people who owe relatively small amounts.

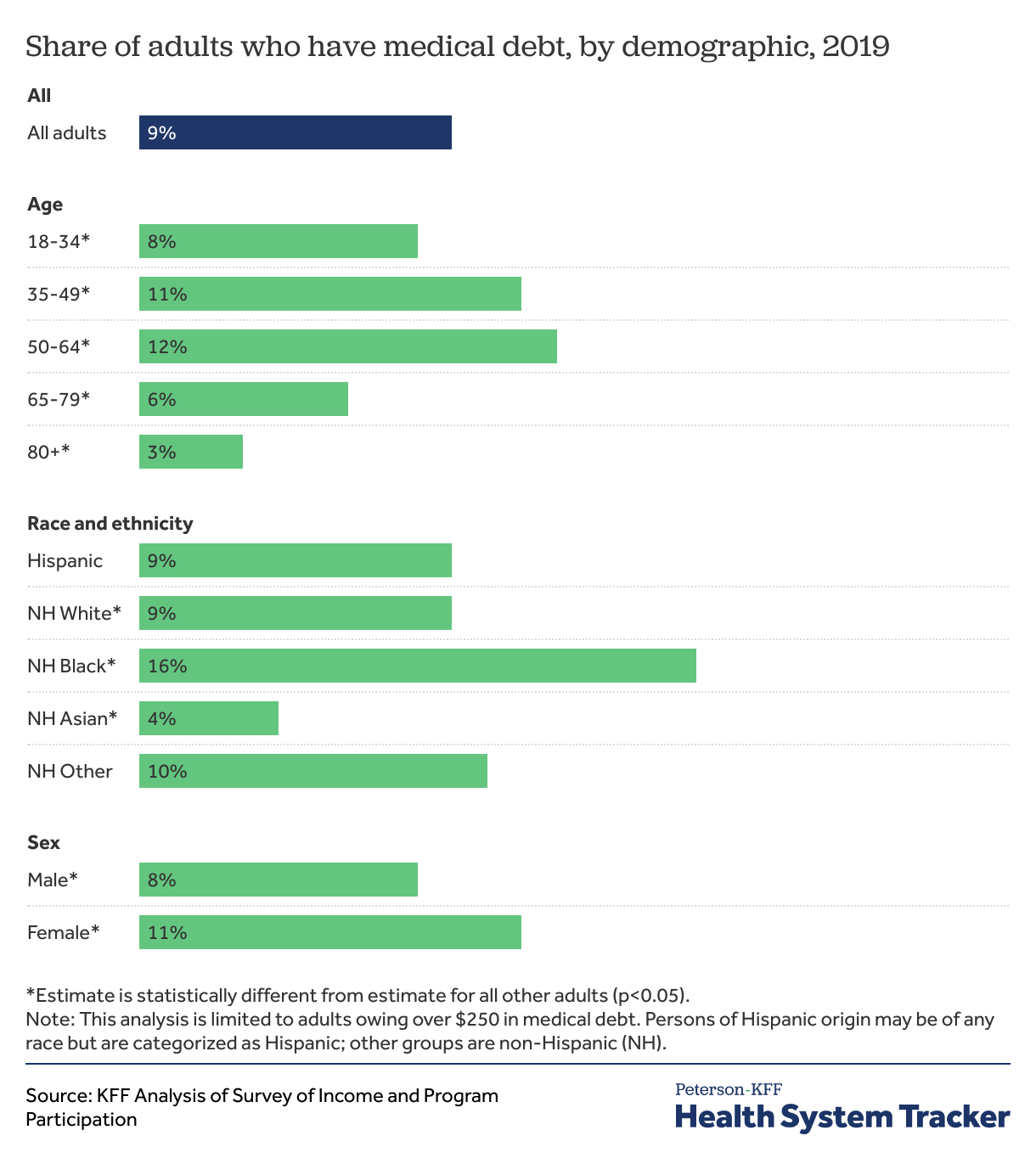

We find that 23 million people (nearly 1 in 10 adults) owe significant medical debt. The SIPP survey suggests people in the United States owe at least $195 billion in medical debt. Approximately 16 million people (6% of adults) in the U.S. owe over $1,000 in medical debt and 3 million people (1% of adults) owe medical debt of more than $10,000. Medical debt occurs across demographic groups. But, people with disabilities, those in worse health, and poor or near-poor adults are more likely to owe significant medical debt. We also find that Black Americans, and people living in the South or in Medicaid non-expansion states were more likely to have significant medical debt.

As we age, we typically use more health care and therefore often have higher health care expenses and out-of-pocket costs. Unsurprisingly, middle-aged adults are more likely than young adults to have significant medical debt. However, the share of adults with significant medical debt decreases when people reach Medicare age. We find that 12% of adults ages 50 to 64 report having significant medical debt, compared to 6% for those ages 65 to 79.

Black Americans are far more likely than people of other racial and ethnic groups to report significant medical debt. We find that 16% of Black Americans report have significant medical debt, compared to 9% of White and 4% of Asian Americans.

Women are also more likely to report having medical debt (11%) than men (8%). Some of this difference is likely related to childbirth expenses and lower average income among women than men.

People with lower and modest incomes are more likely to have significant medical debt. We find that 12% of adults with incomes below 400% of the federal poverty level report having significant medical debt. (In 2019, the federal poverty line was $12,490 for a person living on their own and $25,750 for a family of four.)

Most people in the United States are insured, but adults who were uninsured for more than six months in a year are more likely to report having significant medical debt (13%) than those who were insured the full year or uninsured for half of the year or less (9%).

People with complex heath needs that require ongoing care can see medical bills pile up over time. Those in worse health or those living with disabilities may also experience unemployment or income losses, further contributing to their difficulty affording medical bills. We find that adults living with a disability are more likely than those without a disability to report owing over $250 in medical debt (15% vs. 7%). Similarly, people who report their health status is “fair” or “poor” are more likely to say they owe significant medical debt than those who say they are in “very good” or “excellent” health.

The burden of medical debt is not distributed equally across the country. People living in rural areas, in the South, and in states that did not expand Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act were more likely to report having significant medical debt.

The chart above highlights the interaction between income and health status. Adults in worse health are more likely to report significant medical debt when they are also lower- or middle-income. For example, 23% of people in poor health with household incomes under 400% of poverty had over $250 of medical debt, compared to 16% of adults in poor health with incomes at 400% or more of poverty.

Most of the 23 million adults with significant medical debt owe over $1,000, and about half (11 million people) owe over $2,000. Among the 23 million adults with significant medical debt, about 3 million (13%) have debt obligations between $5,001 and $10,000, and another 3 million (13%) owe more than $10,000.

Approximately 6% of adults (16 million people) in the U.S. owe more than $1,000, 2% (6 million people) owe more than $5,000 in medical debt, and 1% of adults (3 million people) in the U.S. owe more than $10,000 in medical debt.

The total amount of medical debt is difficult to estimate with any precision. While surveys capture a larger share of people and more types of medical debt than analysis of credit reports, there are challenges in capturing data from people who owe high levels of debt. A small share of adults account for a huge share of the total; for example, 0.3% of adults account for well more than half of the total medical debt. In SIPP, the aggregate amount of medical debt owed among the highest debt holders varies considerably from year to year. To reduce the influence of the highest debt holders on the aggregate amount of medical debt, we used a conservative method to calculate the total medical debt for respondents with extremely high debt amounts in SIPP. This approach essentially removes the highest debt values from the calculation.

Using this approach, the SIPP survey suggests that total medical debt for adults with more than $250 in medical debt was at least $195 billion at the end of 2019. This is considerably less than the total we would get if all medical debt reported in SIPP was used, but still much more than the total amounts estimated by others using credit reports.

The Consumer Financial Protection Bureau (CFPB) estimates that $88 billion in medical debt is reflected on Americans’ credit reports, though they acknowledge the total amount of medical debt is likely higher because not all medical debt is visible to consumer reporting companies and those data only reflect debt among people with credit reports (not all adults). Medical debt can also be masked as other forms of debt, for example, when people pay for a medical expense on a credit card or fall behind on other payments in order to keep up with medical bills. On one hand, assessing total medical debt through surveys is difficult because a large share of total debt is held by a small share of people. On the other hand, surveys like the one we analyzed here may uncover medical debt that is not visible on credit reports or is otherwise disguised as another form of debt. Our analysis suggests that the total amount of medical debt is likely much larger than the already large amount of medical debt reflected on credit reports.

Medical debt remains a persistent problem even among people with insurance coverage. Most Americans have private health insurance, which generally requires payment of a deductible, coinsurance, and copays for medical services and prescriptions. A serious injury or illness can cost thousands of dollars out-of-pocket to meet these deductibles and other cost-sharing requirements. For people with a chronic illness, even smaller copays and other cost-sharing expenses can accumulate to unaffordable amounts. Insured patients can also incur medical debt from care that is not covered by insurance, including for denied claims, and for out-of-network care.

Many Americans, even those with private health insurance, do not have enough liquid assets to meet deductibles or out-of-pocket maximums. Among single-person privately-insured households in 2019, 32% did not have liquid assets over $2,000. Among multi-person households where at least one household member has private insurance, 20% did not have liquid assets over $2,000. Additionally, 16% of privately-insured adults say they would need to take on credit card debt to meet an unexpected $400 expense, while 7% would borrow money from friends or family. For these people, even a medical bill for a few hundred dollars can present major problems. KFF surveys and other studies find that people with unaffordable medical bills are more likely to delay or skip needed care in order to avoid incurring more medical debt, cut back on other basic household expenses, take money out of retirement or college savings, or increase credit card debt.

Medical debt can happen to almost anyone in the United States, but this debt is most pronounced among people who are already struggling with poor health, financial insecurity, or both. People who are very ill or living with a disability are also at risk of losing their employment or income due to illness. Shortcomings in both insurance coverage and social safety net programs aimed at replacing income during a time of illness can compound to increase the likelihood that sicker people end up with large amounts of medical debt. There are also significant racial disparities, with Black Americans being much more likely than people of other racial or ethnic backgrounds to report owing significant medical debt.

It is not yet clear how the pandemic and resulting recession affected medical debt in the United States. On one hand, many people lost employment and income early in the pandemic, which could have led to more difficulty affording medical care. On the other hand, many people delayed or went without care, so fewer people may have been exposed to costly medical care. Additionally, there was a small shift from employer-based coverage to Medicaid, which has little or no cost-sharing. Most private plans also voluntarily waived COVID-19 treatment costs early in the pandemic. In total, out-of-pocket health spending in the U.S. dropped by about 4% from 2019 to 2020.

As of January 2022, surprise medical billing is now banned in most cases by the No Surprises Act. However, “surprise bills” represent just a fraction of the unexpected and large medical bills many Americans face.

The fact that medical debt is a struggle even among households with health insurance and middle incomes indicates that simply expanding coverage will not erase the financial burden caused by high cost-sharing amounts and high prices for medical services and prescription drugs.

The Survey of Income and Program Participation (SIPP) is a nationally representative survey of U.S. households. The 2020 survey asked people age 15 and older in the household whether they owe any money for medical bills not paid in full as of December 2019. Respondents are asked to exclude bills that will likely be paid by the insurance company. Households may include non-related persons cohabiting together. Respondents younger than age 15 were not asked about medical debt.

Our analysis is at the individual level for adults age 18 and over. In order to identify households carrying more than small levels of debt, we looked at the share adults (age 18 and up) who reported that they owe over $250 in medical debt. Medicaid non-expansion states include those that had not expanded Medicaid under the Affordable Care Act and begun enrolling expansion eligible people by the end of 2019. People with a disability are those who have difficulty with one or more of the six daily tasks (difficulty with hearing, seeing, cognitive, ambulatory, self-care, or independent living). See the SIPP technical documentation for additional details.

The Peterson Center on Healthcare and KFF are partnering to monitor how well the U.S. healthcare system is performing in terms of quality and cost.